With the election of a new leader and ruling party, there will be a changing of the guard at the head of New Zealand’s government this year. Former businessman and leader of the centre-right National Party, Christopher Luxon will now lead the country.

With that and Waitangi Day on February 6th, we thought this an apt time to consider New Zealand’s constitution and how it began with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in February 1840 between Maori Chiefs and representatives of the English crown.

How did the Treaty of Waitangi come to be?

To answer that question, we need to look at life in New Zealand prior to 1840.

New Zealand in the 1830’s was a period when sealing gangs (including ex- convicts, escaped convicts and deserters) were involved in a series of confrontations with Maori people.

Maori tribes were involved in inter-tribal wars called the “Musket Wars”, but it was also a time when missionaries from Britain were establishing an Anglican mission in the Bay of Islands.

And, indeed, it was from the Bay of Islands that Maori chiefs petitioned William IV for protection by Britain from its subjects (and from French ambitions on the South Island).

Token intervention began in May 1833 with the arrival of James Busby as British Resident.

He and his family set up home (now called the Treaty House) on a farm that they established at Waitangi and Busby, as a civic official, was to be a “police officer” for the area. However, he had no army with which to enforce a rule of law and became known to the Maoris as “the watch-dog without teeth”.

Into this mix came the New Zealand Company, set up in England in 1837 to colonise and profit from the lands of New Zealand.

With events moving at pace and the dangers of a free for all land grab, the British Colonial Office intervened to ensure law and order in British enclaves. In this way, humanitarianism and the need to provide a land bank for the Colonial Treasury (and not for private operators) was established.

The Arrival of Governor Hobson

Hobson became governor on July 30 1839, with the task of overseeing the British in New Zealand. In January 1840, he arrived in the Bay of Islands and quickly created a treaty for Maori chiefs, this treaty aimed to establish peaceful coexistence between Maori and pakeha (non-Maori).

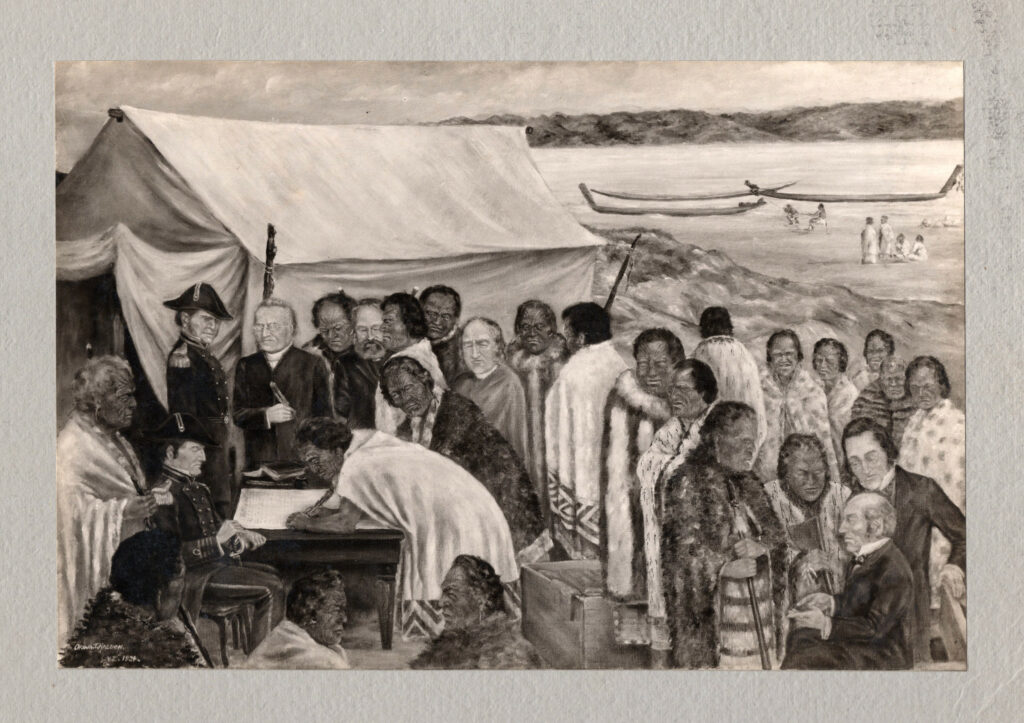

The Treaty was prepared in just a few days, it was then translated into Maori overnight on February 4th by missionary Henry Williams and his son Edward. About 500 Maori discussed the treaty for a day and a night before signing it on February 6, 1840.

Hobson and others emphasised the benefits of the Treaty while downplaying its impact on Maori authority. Many chiefs supported the agreement, believing it would strengthen their status.

On February 6th, about 40 chiefs, led by Hōne Heke, signed the Maori version of the Treaty. By September, another 500 chiefs from around the country had signed copies of the document. Some were uncertain but signed anyway, while others refused or didn’t get the chance. Almost all signed the Maori text. The Colonial Office in England later declared that the Treaty also applied to Maori tribes whose chiefs had not signed. British sovereignty over the country was officially proclaimed on May 21st, 1840.

The Treaty

In basic terms, the Treaty is a broad statement of principles the British and Maori made as a political pact to found a nation state and build a government in New Zealand.

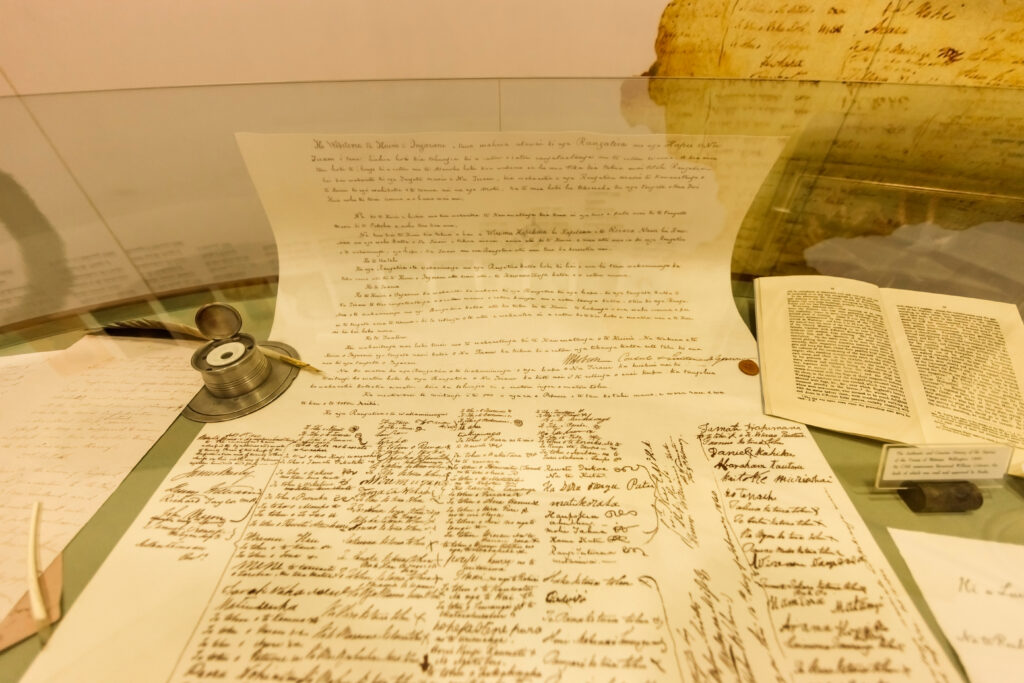

The document has three articles. In the English version, Maori cede the sovereignty of New Zealand to Britain. Maori give the Crown an exclusive right to buy lands they wish to sell, and, in return, are guaranteed full rights of ownership of their lands, forests, fisheries and other possessions; and Maori are given the rights and privileges of British subjects.

The Treaty in Maori conveyed the meaning of the English version, but there are important differences. Most significantly, the word ‘sovereignty’ was translated as ‘kawanatanga’ (governance).

Some Maori believed they were giving up governance over their lands but retaining the right to manage their own affairs. The English version guaranteed ‘undisturbed possession’ of all their ‘properties’, but the Maori version guaranteed ‘tino rangatiratanga’ (full authority) over ‘taonga’ (treasures, which may be intangible).

Maori understanding was at odds with the understanding of those negotiating the Treaty for the Crown, and as Maori society valued the spoken word, it’s fair to assume explanations given at the time were probably as important as the wording of the document.

Disputes after the Signing of the Treaty

After the signing of the Treaty, there was a huge increase in the number of Europeans wanting to buy land and settle in New Zealand.

However, problems arose when new settlers (or companies representing them) tried to buy land without consulting all of the Maori landowners. Many Europeans had no understanding of the concept of ownership of the land by the tribe.

The Maori people also gradually realised that they were not free to sell their land to anyone, and that under the terms of the Treaty they could only sell to the government, and not to anyone else if the government did not want to buy it.

Land sold to the government was sold on to settlers, usually at a much higher price than that received by the Maori owners.

Despite assurances by the British Government that Maori people owned all of New Zealand, not just the lands they occupied, within a few years the pressure from new settlers for land led to the taking of unoccupied space, described as wastelands by the Crown.

The New Zealand Land Wars

As settler demand for land grew, and it became more obvious that the British expected Maori to be subject to British law and authority, tension erupted into what is now known as the ‘New Zealand Wars’.

The conflict took place mainly in Taranaki, Waikato, Hawke’s Bay, and Auckland. They were generally fought between 1843 and the 1870s, with one result being that the government confiscated large areas of land from the Maori people.

As more settlers arrived into New Zealand and representative forms of regional and national government were formed, the principles and spirit of the Treaty were largely ignored and pakeha encroachment on Maori lands and culture continued through the late nineteenth century and into the twentieth.

The common view was that much of the Maori land was not used for ‘productive’ purposes and was therefore ‘wasted’. When Europeans obtained land, they immediately turned it ‘to good account’. Such attitudes and policies contributed to the fact that Maori held less than 15% of the land they oversaw in 1840 by the turn of the century.

The Waitangi Tribunal

By the 1960’s there was growing sympathy amongst the Pakeha majority towards Maori claims of dispossession of lands and the removal of the rights they had assumed lay in the Treaty’s conditions.

The Treaty of Waitangi Act was passed in 1975. This gave the Waitangi Tribunal the powers to investigate any Crown breaches of the Treaty in the future. In 1985 this was extended, so that claims could be brought about cases that had existed since 1840.

How the Waitangi Tribunal Works

The Waitangi Tribunal investigates claims by Maori against any act, policy, action or omission that affects them in a negative way. The Waitangi Tribunal is instructed to make its decisions based on both the English and the Maori text, as both were signed, even though by different people.

Where there is any doubt about the meaning of the text, according to international law, the indigenous language text (in this case Maori) comes first.

However the Tribunal must also take into account the cultural meanings of words, the circumstances of the time, comments made then, and the objectives of the people who made the Treaty, so that practical solutions that support the spirit of the Treaty can be found and made to work today. The Waitangi Tribunal only has the power to make recommendations to the government.

Ultimately, it is the government who makes the final decision on what is to happen, and whether the Tribunal’s recommendations will be carried through.

We hope you’ve found this very brief history of the Treaty of Waitangi insightful, while there’s a lot to unpick, it’s a fascinating history and definitely worth exploring if you plan to take a trip!

If you’re planning to take a New Zealand holiday and want to visit the Bay of Islands in early February, be sure to have your accommodation pre-booked in good time! On the 6th February celebrations to mark the signing of the treaty take place and the event draws thousands of attendees. Just give us a call if you’d like to find out more about the best course of action.